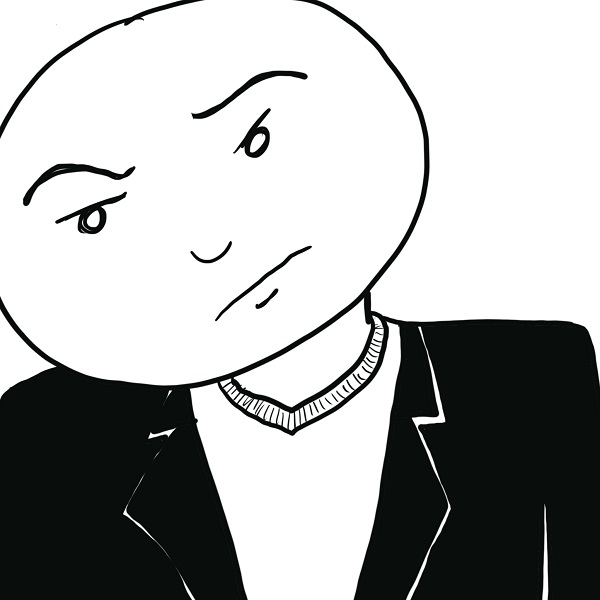

There are no dirty looks on the internet

It's much easier to be hostile or vitriolic online than it is in real life, so much so that a related and maybe even more important problem persists: it's also very easy to be gauche. In fact there's almost no consequences for being gauche.

Have you ever wished you could just give someone an irritated look through a computer screen? Like, invite them to Skype, do nothing but let out a very long sigh and then hang up?

That would be amazing.

Wrong, awkward behavior, the sort that's just a little bit inappropriate, is prevalent online. So much so that many of its exhibitors don't really know it's so. In fact, if directly confronted with the behavior's gaucheness, the exhibitor would likely protest. They would defend it with a string of words that might even sound reasonable, but the behavior would still be collectively destructive.

A shared consensus around right and wrong behavior can drive conformity, it's true, but it can also lubricate social interaction. It can make the world more welcoming to new people or for outsiders to pop into and out of with less stress.

The internet can be very stressful. A broad theme on Twitter, as of this writing, is how everyone ought to leave Twitter. We aren't because a lot of fun stuff still goes up on there and also we have this vague feeling that it doesn't have to be this bad.

Nadia Eghbal, a writer I always like to read, raised these questions this week with a blog post where she dug into a book that may well be the smartest book ever written ever by anyone, The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs.

Please click the link above and have a look at what Eghbal wrote. It's really good. It covers a lot of ground. Rather than summarize it here, it's better to just take the whole thing in. And if you care about cities or public life in general, Jacobs book is worth anyone's time.

Eghbal basically argues that online spaces should be treated much the same way we treat sidewalks and parks and other shared spaces, but we behave much worse in public spaces online than we do out in the real world. She writes.

Given the state of our public streets today, most of us head straight for the hills, confining our ideas to private conversations with trusted friends, rather than risk exposing ourselves.

And before you start nodding here, I want to be clear: Eghbal isn't just talking about the trolls. She's talking about the people who pile on others for supposedly "good" reasons. Many of the people who are angry at the people shouting online "I hope you die" probably also encourage other online behaviors that are just as destructive, if not so barbaric.

So go read the blog post. I agree with everything Eghbal wrote and here I want to play it out a bit.

In the following I'm going to develop the argument for a new kind of feature in social media that has the potential to improve the social feedback loops online. Then I'm going to point out why it could very well be wrongheaded thinking. But I still like the idea.

Call me a techno utopian.

What's missing?

OK, so in short Eghbal talks about some principles that Jacobs observed in her research on city life. Eghbal draws a parallel between what Jacobs calls "sidewalk life" and life online. Eghbal observes:

When sidewalk life thrives, we can have meaningful exchanges with strangers without the expectation that we will become intimate friends. We may interact regularly, and even feel an affinity for one another, but it’s understood that this needn’t transfer to our private lives.

On the sidewalk, Jacobs writes, we are in "public" but that doesn't mean anything goes. We all understand that it's not okay to stop people will nilly. It's generally not okay to jump into the conversations of strangers. We shouldn't dance naked because a song we like comes on the radio, even though we are generally welcome to do that at home.

It's not entirely clear how we learn all these lessons. Some of them we learn growing up but some are pretty subtle. Yet norms persist, get passed on and generally people follow them. It makes sidewalk life nicer. We can enjoy seeing strangers, taking in snippets of people's private lives, occasionally chatting with strangers without the undue burden of feeling that we are revealing too much.

Online, though, people behave much more presumptuously. Eghbal gives some good examples here so again, please check out what she wrote.

Reading the post, it really got my mind cooking: why haven't better social norms come up online? The internet has been a major part of our lives for two decades or more now (depending on who you are talking to, of course).

There are two relatively simple norms that I have seen folks push on for years now that really haven't stuck. First, pushing email users to be more careful about the use of the "reply-all" function and second asking both parties to a potential introduction before making it.

both of these have been brewing for at least a decade. Culturally, they have gone nowhere.

Why?

Further, these days I think most reasonable people would agree that a new kind of gauche behavior has taken over online: attacking anyone who fails to abide by a prevailing ideological structure about discourse. Since I tend to live in a left leaning world, I see this take leftist forms a lot. Jumping on anyone whose comment could be possibly viewed as less than perfectly "woke."

In fact, lots of people do this and they encourage others to do it with likes and shares, but it's a fair bet that the folks who approve of this behavior are a small but vocal minority of internet denizens.

Minor aside: odds are you have heard about "the ratio" on Twitter. The basic idea is this: if a tweet is getting twice as many replies as it's getting retweets, then the person probably pissed off the internet.

So, we actually have this situation where the act of providing an actual reply, real dialogue, is beginning to signal negativity. The gold standard is the silent echo.

But even though a general consensus prevails against these behaviors, a norm against them hasn't taken hold. Why not?

And a quick aside that I'm only going to write because this is the internet and I know how dialogue online works. To the objection:

Wait, dude, are you writing all this because you are pissed about "reply all"?

No.

My point is that if we can't establish a norm against something so simple and direct as "reply all" how do we expect more subtle manners and norms to develop online, the kind that help people muddle their way through less cut and dry cases.

The candy store guy

One of the stories from Jacobs' book that Eghbal revisits is that of a candy store owner in the East Village at the time Jacobs wrote.

The candy store owner is what Jacobs' calls a "public character," and Eghbal translates that to people online that others collect around. For example, I wrote about this cryptocurrency called "kin" a while back, and while covering it I learned that there was this one member of the community who was super well known. He always took time to explain things to new people.

He was an online candy store owner. Both were public characters.

So in Jacobs story, she explains that the candy store owner knew lots and lots of his customers, but he would never introduce them to each other. This wasn't a decision he made. Not doing that was an obvious violation of a norm to him.

I try to imagine how a norm like that takes shape, and I think it's pretty simple. If he did introduce two people he knew had something in common in his shop, they would non-verbally indicate to him that it was a weird thing to do. He would feel weird. They would feel weird. It would be a negative experience for everyone.

Yet the text of the interaction would all be positive. No doubt if you read a script of words said in the introduction, it would seem very banal. But maybe one of the two people would give him an ambiguous look. Or their bodies would tense up.

Whatever it was, no one would have to get mad or confront anyone, but a lesson would have been learned.

You can't do that online.

Ephemeral digital responses

On the internet, if you say something to me and I think it's inappropriate, I can't give you a "look." A look is ephemeral. Even if I reply with an emoji, that emoji is there forever. And that permanence gives it more weight, it makes it more aggro. The other person can point to it forever.

This makes it much harder to express displeasure online without it becoming, as the kids say, "a thing."

So here's where I get to my technical proposal: social media should have a way to respond ephemerally. When you open your Twitter interactions page, your past tweets should just flash for a moment with the avatars of respondents and maybe just an emoji or a color.

What if you posted a tweet and when you came back to Twitter 20 of your friends had responded with RED. That tweet flashed in twenty red rows with lots of your friends' avatars for a couple seconds and then the bands were just gone. Maybe you weren't even sure which of your friends had responded? And you couldn't doublecheck. The red bands over your tweet were there and they were gone.

All you know is you got a big brief blast of red. What does red mean? Oh I think we know.

Maybe this isn't the right UX, but I think the fact that all responses online are there forever is a problem. We need a way to respond in passing. With something ambiguous and brief. Something that would give us a low stakes way to say "that was great" or "dude, stop it."

Now here's the problem with my idea: we have a problem of human interaction and I'm proposing a technological intervention.

I know, I know. It's maybe wrongheaded.

It would be better if messages like Eghbal's got through and people just reflected more on their behavior.

But I keep coming back to "reply all." "Reply all" is so bad that I've seen posters in offices reminding people that it's bad, and yet and yet and yet... reply-all-apocalypses still go down. Our inboxes still get inundated with updates about projects that barely matter to us. It doesn't stop.

So if that simple idea can't get through how can more subtle ideas make it? How can we get a better barometer for when it's time to call someone out and when maybe we should cut them a break?

I think we need a way to roll our eyes online, but to do it in such a way that the other person sees it, but maybe they aren't 100 percent sure they saw it. Or what it meant. And anyway they only get to see it once and it's gone.

Ephemeral responses on social media could give more people a comfortable way to express themselves, and that could make a big difference.

Isn't it worth a shot?

—Brady Dale

January 27, 2019