When they stamp their feet

Every few years some startup comes along that wants to "use data" to help voters to "discern" which candidates they should support. The faster these startups die the less time gets wasted by everyone. People know where they stand.

I assert this as someone who has talked to hundreds and hundreds of people one-on-one, at length, about their political views. I did it professionally as a community organizer literally for a decade. I talked to all kinds all over the country. People know.

Whether they are invested enough in their communities to act on their views is another question, and I may have hit on a way to help map out which people are the most likely to take action.

So let's do something of a "literature review" here. It helps to think as accurately as you can about your own views and to create a framework around how you think about the views of others. Right and left mostly cover it. Generally speaking, if someone tells you that they are conservative or liberal, you know where they stand on most issues that might come up in Congress.

For example, right and left, when it deals with how the state should handle its citizens' money, asks whether governments should collect a lot of it (maybe even all of it) and spread it around (left) or should it collect the bare minimum to keep basic communal services that everyone agrees on (firefighters, roads) working (right)?

[ASIDE: there is a view that when you go far enough in either direction you end up at anarchy either way, but I think this is silly and I don't want to entertain it here.]

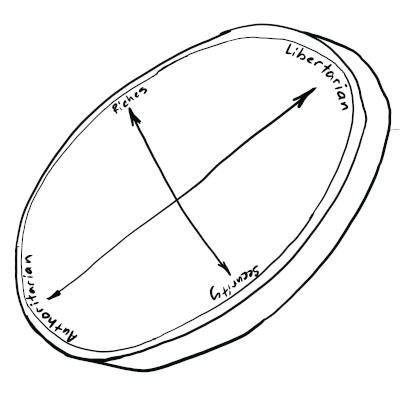

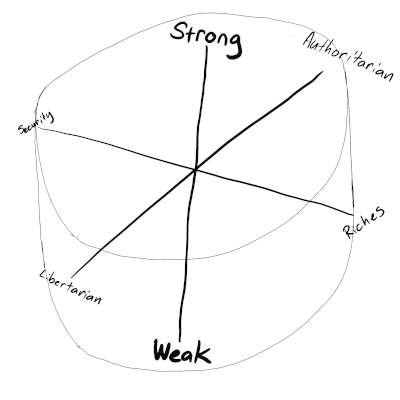

So right and left works well, but maybe you have heard about the political compass? The political compass rightly points out that really we tend to have another less clearly thought about dimension to our political thinking. That is, do we think in terms of individuals or do we think in terms of groups? At the very extreme, this becomes libertarian versus authoritarian.

In a libertarian world, there are almost no rules. A lot of times it's phrased as just don't hurt anyone violently (hurt them all you want with pollution and risky behavior though, that's fine).

In an authoritarian world, people are just organs in a giant organism that is the state. They matter individually no more or less than how well they serve the state.

This is all well and good and very helpful. I have no criticism of this framework. Again, if you ask someone just a few more questions you can pretty much locate them on the compass and you can probably guess where they will fall on almost any political issue that comes up.

(ASIDE: As I think I have said before, I don't actually believe that anyone feels or thinks just one way about — really — anything, but still... people tend to broadly sort out where they stand such that their public engagement remains predictable, even if they nurse doubts, so this framework remains pragmatically useful.)

But all the compass gives you is a binary view. Would they check "yes" or "no" on a box? This isn't that useful, though. The real question is: How far will they go?

If all that mattered was how many people support something, America would have had gun control. The trouble is the many people who support gun control won't go as far to enact it as the minority that opposes it.

But then yesterday I started thinking about the curious fact that so many of the most conservative places in the United States are the ones who benefit the most from government services. How can that be?

I think I have a helpful way to start thinking about this.

There's been a number of proposed third dimensions to this political compass, and a lot of them are interesting, but none of them, in my mind, nail it like the first two dimensions do. The others are more like fun trivia.

But something was needling me about the fact that so many poor folks in America stan for Trump and have otherwise largely backed an agenda that seems to be against their best interest. On some level, what is missing is a personal axis, one that is not about how a person feels or thinks but about their actual situation.

At first I thought of this Z-axis as rich versus poor, but then it occurred to me that there are a variety of contexts where this framework works with slightly different wording, but rich and poor doesn't make sense in the others. So what it really always comes down to is "strong" and "weak."

So in the politics of money, rich is strong and poor is weak.

Similarly, imagine the spectrum for sexual politics, which is one sphere that seems to operate somewhat independently from electoral politics (you can be a conservative politically who leads a pretty wild sex life, for example, and a kale-smoothie-drinking liberal who rocks it totally vanilla). In that case, you can imagine an X-axis that's more about the amount of sex you have: from celibate to libertine. The Y-axis would be more about who gets to decide about sexual rules: personal choice versus public mores.

You might be thinking, okay but what would a highly libertine but also highly public mores based system look like? It would look a lot like this very weird company, OneTaste, that bilked people for years, I think. OneTaste basically insisted that employees have lots of sex with each other, because they had an enforced libertine ethic. We don't see this setup often, but it happens.

On the flip side, a person who bothers to refer to themselves as "asexual" is a celibate who embraces personal choice. He buys the whole discussion of wild spectrums and has named himself within that rich continuum.

So, anyway, the Z-axis for sexual politics would be "super attractive" (strong) and homely, awkward or worse (weak).

Can we agree on this? OK I just wrote about sex so someone is definitely pissed off. Sorry (ish)! Skip back up to "At first I thought" if you're feeling salty and then jump to here when you see the bold words: strong and weak.

What does this new Z-axis mean, though?

Well, here's what I think: I think the Z-axis doesn't really tell you anything about what a person believes. I think the Z-axis tells you something about how fiercely they believe it. Basically, I think there is an inverse relationship. If your beliefs run counter to your interests, you are very likely to cling to them more tenaciously and act more strongly in defense of them.

This may sound counter-intuitive but I don't think it is. First of all, if your beliefs match your interests, then they likely match those of people you know. Why get ferocious about something when everyone you know agrees with you?

Second, if you have no cognitive dissonance around your beliefs, then you have fewer nagging doubts to overcome. People act out when some part of them suspects they are wrong.

Oops I'm going to talk about sex again! Tricked you! Let's imagine a very beautiful sexual libertine who thinks intimate matters are really all about personal choice. She knows she can have all the partners she wants and very few people are ever very likely either to turn her down or even refuse anything she wants to do with them, so this is a very easy position for her to hold. She's unlikely to be very fierce about this stance, though, because she might almost be embarrassed about how easy all this is for her.

She is, in other words, very strong. She knows others cannot always get what they want, but she can. She's likely to be the sort of person who just agrees with anything anyone says to her about sexual topics because she knows she's going to have the life she wants anyway. Why fight for it?

I think this is why societies just sort of muddle about to some kind of marriage structure, which is close enough to universal. Most people are pretty average looking and know that the libertine lifestyle isn't really an option for them, but hey! If we all sort of agree to a monogamish norm then probably each average person will end up with someone. The super hotties won't really fight it because they will still get what they want anyway and the uggos will probably support it too because it gives them a better shot at getting laid anyway (even if they don't).

Everyone in a very mild way shambles toward a rough nuclear family centrism without really talking about it. Many weak effects yield a banal, not especially fiercely held norm that frays a lot at the edges.

In the same vein, imagine someone who is rich, believes in low taxes and government services but still a high amount of state power. This person could probably be described as "corporatist," someone who largely thinks that big businesses should run most everything that matters and the state should just be there to ease their business dealings.

A wealthy person with this viewpoint is acting on his self-interest, and he is likely to stay behind closed doors, give money where his hired lobbyist tells him to and stay out of the papers about it as much as possible.

On the flip side, we have someone like George Soros who is very rich but pushing an extremely pro-state, liberal agenda. He's out and proud and putting piles of money where his mouth is in a very public way. He knows it pisses off his peers, so he digs in his heels, goes public and seeks moral support elsewhere.

Similarly, when you see economically stressed people backing Trump, they ignore facts, call the media liars anyway and focus on his personality and what he represents for them. It actually makes sense to do this when you frame it as determined by social capital.

People get defensive, and defensiveness leads to anger. Anger yields action. Every organizer knows this.

When you consider that on some level poor people who back the harshest Republicans know on the inside that someone like Trump wants to tear down things they depend on, it's not enough just to show up and vote for him. A person needs to yell about it in order to drown out the sound of their own inner doubts.

This Z-axis is actually useful, because it predicts recalcitrance. I'm not sure what you do with that understanding yet, but the first step to dealing with a dilemma is making it legible.

—Brady Dale

December 27, 2019